Long read

By Carolina Pineda Arcila

Responding to Trauma

There had been rumors that they were going to take over the town. We didn’t know whether it was true, but we were living in constant fear. For a while now this armed group has been gaining control in the area and their power continues to grow. We hear that their leader has a lot of power and we already know that they are the ones in charge around here. This army has killed people, taken their land and threatened families. They have taken children and recruited them, and taken strong, youngmen to be part of their army.” “It was night-time when I heard strange noises outside my house. Through a crack in the door, I could see armed men who were taking families out of their homes. I also saw men burning houses and looting my neighbors’ property. Everything was being destroyed. With a crash, they broke down the door of my house and a group of men came in and took us by force, my children, my wife and me. We were forcibly displaced; we were left with nothing.”

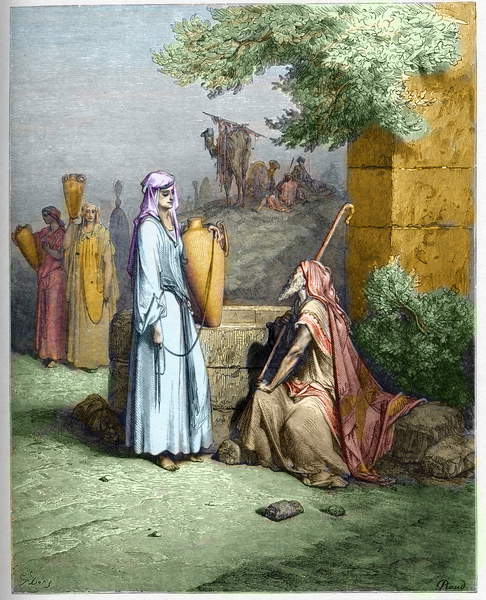

“My name is Eliezer, I am an Israelite from the tribe of Judah and a member of the royal council. My family and I, we had to leave our land and were forced to settle in Babylon… where we could not conceive of a better future than what we had in our land; we still yearn for what we left behind.” (Inspired by 2 Chronicles 36:5-21; 2 Kings 24:1-25:21; Jeremiah 29:1- 2; 52:1-30.)

This story of exile is the tale of many Israelites from the tribe of Judah who were forcibly displaced when Nebuchadnezzar’s army conquered Jerusalem and took with them all the powerful families from the city, after destroying everything in their path. Though the Bible doesn’t mention an Eliezer in the tale of the exile, this is how the events may well have played out, and it is a story exiles around the world recognize. As we read Eliezer’s story, we think of our contemporary context, maybe even our own lives. Just as an example, my native Colombia has been facing a forced internal displacement for the past sixty years due to the armed conflict, with millions of Colombian “Eliezers” among us. As we can see, there are millions of “Eliezers” around the globe. Each one has a different story and a different background, but all have endured these situations one way or another, facing death, fear, and hunger. Some have also received mercy, grace and care.

As a Colombian who identifies with Eliezer’s story, I can share that overcoming forced displacement is not easy, but it is possible. After living through forced migration, there is a sense of uncertainty and fear. It is difficult to trust again. This can make it even more difficult to rebuild a new life in a new place.

Many of the emotions, thoughts and feelings that one faces while experiencing displacement can be called “trauma”. The story of the Israelites presents a scenario that caused trauma in the people who lived through these episodes. In the same way, we can say that as we face forced migration, we are also experiencing trauma. But that does not have to be an obstacle to rebuilding our lives and recreating connections in our new communities. There are different ways of responding to trauma, different ways of healing from it, of coming to terms with it and of finding hope. One way of doing this is through trauma narratives. This involves using Bible stories to show how the Israelites (or other people in the Bible) faced and overcame trauma. Then we put what the Israelites learned into practice in our own communities or in populations that have experienced trauma due to forced migration.

As an example, let’s look at Jeremiah 29, when the prophet advises the Israelites to stay and settle in Babylon (verses 5-6); to seek Babylon’s welfare and pray for it, although Babylon is its direct victimizer (verse 7). This could be used as a trauma narrative to promote healing, reconciliation and hope in the lives of people facing forced displacement. How does that work? If we think about Eliezer reading this letter, we can reflect on the impact these words had on him and his life. He is reading this after all his belongings had been destroyed, his town was burned, and most likely after his family was divided – some of them possibly even killed. And what does the prophet say? “Go ahead… rebuild, replant, start again, promote what is good for that place and pray.”

What does this mean for us today? When looking at any Bible passage, we can ask these four questions in order to analyze it as a trauma narrative:

- What happened?

- Who were the victims?

- Who were the victimizers?

- What should be done?

If the passage answers these questions, then we can proceed to answer those same questions in the forcibly displaced reality that we are currently facing (Jeremiah 29 tells us what happened, the victims and victimizers, verses 1-4), 5. And then it says what it is to be done (verses 6-7). Now we can think of a specific scenario, for example the Colombian displacement, and apply this pattern: we can follow the prophet’s advice and rebuild, replant, start again in the new place, promote what is good for the new place we are living in, and pray. By doing this with multiple Bible stories we connect our story to the experiences of God’s people. We find God’s voice guiding our actions in a way that brings healing, reconciliation and hope. We find a way to reconcile with the idea that we can start again in a new place, even when it is a place that has victimized us. This involves praying for and building up the place where we are. We reconcile with the idea that we are active citizens who can be a blessing to a new community, and reconcile with those who have caused us so much harm. We reconcile with ourselves and with others. Because God says, “I alone know the plans I have for you, plans to bring you prosperity and not disaster, plans to bring about the future you hope for” (Jeremiah 29:11)